Just heard from the O’Reilly folks that the book has entered production, which is pretty exciting. That should put the release date to be the end of August, if all goes to plan. You can now pre-order it from bookstores everywhere.

For now, here is a sample from Chpt 4: Building Trust into Mobile Payments. Enjoy.

Building Trust into Mobile Payments

One of the key tenets of human computer interaction is to avoid inciting anxiety in the user, which can be caused by uncertainty about negative events[1]. This is especially true when dealing with peoples’ hard earned money. Eliminating that uncertainty with design is a matter of finding out what your users expect from an experience, and catering to those expectations as much as possible, using common user interfaces that the user will recognize. With nascent technology like mobile payments, there are less abundant examples of successful design patterns, than say for e-commerce shopping carts or browsing a social network feed. Still, there are some emerging patterns and best practices that one can to look to as a good (or bad) example.

Don’t Design for Early Adopters, Design for Everyone Else

Mobile payments are not really a new thing. Consumers in places like Japan and South Korea have enjoyed immensely popular mobile payment initiatives since 2004, beginning with services like FeliCa and NTT DoCoMo’s osaifu keitai (“wallet phone”) with transaction volume surpassing ¥1 trillion by 2007[2]. They have also been using the same phones as door keys and airline boarding passes. So now that all these technologies exist in the mobile space, how come we aren’t using them every day here in North America?

The easy answers to the adoption question are generally centered around the fact that swiping a plastic card still works (mostly) and chicken-and-the-egg scenarios: mobile payments are built upon an outdated financial infrastructure[3], or merchants won’t adopt new point-of-sale technology, or that telcos like those in the Isis collective have placed a chokehold on the mobile ecosystem. These are of course valid challenges, but I see a much broader, more difficult challenge: consumers are not yet entirely comfortable with idea of using their phone to pay for things.

There are many points in the mobile payments supply chain that present technical challenges to adoption: compatible phones (in the case of NFC), point-of-sale upgrades (like QR Code scanners and NFC readers). NFC in particular requires business relationships between the bank and the mobile network operator, which are not always harmonious. Once the user has the right phone, then gets their card on their phone or links it to their app account, there’s no guarantee their favorite merchants will even be able to accept a mobile payment. All this makes it hard for a user to start using their phone to transact, even if they were totally on board with the idea of their phone having access to their bank account in some way. Institutions in the related verticals (financial services, telecommunications, retail operations) don’t typically work together, unless they see a compelling consumer demand for a new payment method. The reason why NFC has become popular in places like South Korea is thanks to close collaboration between these disparate parties to bring new technology to the consumer. In the U.S., there are signs of joint ventures at this scale, like Isis (the three major MNOs) and MCX (retail brands), which are starting to inch the bar forward in terms of commercial visibility. In the end, I don’t think it matters if the impetus of a payments revolution begins with a start up, or with a respected financial brand, but what is clear is that industry-wide initiatives to improve payment technology would be a large contributor to mobile payments becoming more widespread.

Even if the stars of the mobile payment ecosystem align, there is still one key element that is less tangible, but can make or break a mobile wallet, regardless of the method it uses (cloud, NFC, barcodes, etc). That element is the consumer’s trust in the experience, and I feel it is the largest hurdle that mobile wallet designers and developers must tackle in order to build a successful payment system.

Of course, all new inventions must overcome the growing pains of gaining consumer mindshare, just as using the Web to shop, date, and rent vacation homes was slow to be adopted widely when they came to market. If someone had asked me five years ago that banks would be banging down my company’s door to get mobile check deposit (taking pictures of checks and depositing them digitally) built into their banking apps, I would have questioned their sanity. One great example of this is when University Federal Credit Union, the largest financial institution in Austin, Texas, first launched mobile deposit capture in their banking app. Within the first eight months, their members used their phones to deposit $16 million in checks[4]. These days, most major banks have this feature, with very similar usage figures. It’s in our nature as humans to be skeptical of new technology, but this skepticism is not impervious. We are of course capable of change, if its to adopt something that is convenient, reliable and improves our daily lives in a profound way. Over time as we try new gadgets or ways of doing things, we begin to trust them – if they work the way we expect and don’t provide cause for grief. Consider how often you do any of the following now, versus ten years ago:

- write a check?

- balance a paper checkbook?

- print out an online map for driving directions

- visit your local bank branch?

- use a pay phone?

My favorite quote on our capacity to adopt new ways of doing things, when it comes to the financial world, comes from Susan Crawford, Harvard Law professor and past advisor to President Obama on technology and innovation policy:

“There is nothing more imaginary than a monetary system. The idea that we solemnly hand around printed slips of paper in exchange for food and water shows just how trusting and fond of patterned behavior we human beings are. So why not take the next step? Of course we’ll move to even more abstract representations of value.[5]”

The sea change inherent in mobile payments will not happen overnight. These new interactions face an entirely unique and complex adoption challenge because these apps intend to revolutionize a common task that we all do several times a day: purchasing something or paying someone. One criticism of mobile payments (often directed at NFC, but applies to any mobile payment method) is that it’s a solution looking for a problem. This point rings true – as of today, most consumers are just fine with swiping a plastic card. The current system works fine, even if its running on decades-old technology. Its generally reliable, as long as the magnetic stripe on their card hasn’t worn out, and the store’s card readers are functioning properly. No one could argue that there is a pretty low learning curve to using cash or cards. If consumers do eventually switch to paying with a phone, their mental model will remain rooted in the stimuli of the brick-and-mortar checkout experience: wait in line, the cashier greets you, open a leather wallet, swipe a card, tap a PIN number, the register beeps, take the receipt, pick up the bags, etc.).

What’s even more daunting is that we are talking about combining two very personal objects: our mobile devices, and our money. We never leave home without them – though I think that our phones might be dearer to us (recalling a Stanford student survey in 2010 found that 69% would be more likely to leave their wallet at home than their iPhone[6]). Both of these hold significant places in our lives, and compromising either of these is something most of us would like to avoid at all costs. Likewise, consumers are understandably concerned with their financial privacy in this new paradigm. Like me, if you are reading this, you probably feel that mobile devices and money go together like chocolate and peanut butter, but it’s important to keep in mind that not everyone feels this way. Before the user taps that “Register” button on a registration screen, they need to have assurances that the provider of the mobile experience will protect their money, and that they will not be exposed to fraud or information privacy breaches. Once that faith is broken, it’s nigh impossible to earn it again.

It is a whimsical schism that mobile payments are so un-trusted by the general public, when traditional payment methods like cards and checks are in fact much less secure, and easily compromised or faked. Sure, a user’s credit card has a magnetic stripe or an encrypted gold chip that locks down the account number and payment data, but what happens when someone steals their wallet? When was the last time a sales cashier asked to see the back of your card to verify that your signature matched? Are you one of the 12.6 million consumers who has had their identity stolen and used for unauthorized purchases[7]? Consumers are now more wary of their financial privacy than ever before – the Unisys Security Index in May 2014 found that 59% of Americans were extremely worried about hackers obtaining their card details. Financial fraud was their greatest concern, even greater than terrorism (47%), epidemics (34%) or going broke (30%)[8].

Consumers have good reason to be worried. Even large retail brands struggle with the assurance of security, as Target saw in December 2013 after their registers were hacked and cardholder information was compromised. The discovery of the Heartbleed attack of OpenSSL in early 2014 breached the passwords of many high traffic web sites (Facebook, Google, Amazon Web Services). These high profile security breaches only contribute to the fear that hackers are out there chiseling away at the walls that keep consumer information from falling into the wrong hands.

So, mobile commerce has an uphill battle to fight. Of the mobile wallet usability testing sessions I have observed or moderated, an overwhelming dichotomy emerged, no matter how many users were able to complete the test’s payment tasks successfully, or how nice they thought the animations looked. Users generally fell into one of two camps:

- Early adopters

Love the futuristic sexiness of buying stuff with their phone. Had previous experience using the Starbucks app, PayPal or Square. - Everyone else

Ranging from feeling “mildly apprehensive” to “scared shitless” at the thought that their credit card number is stored inside a technological black box that they had never heard of, and didn’t understand.

There are of course nuanced subgroups in each of these, but the second group: Everyone Else, is who as designer need to reassure, particularly as we build onboarding and payment interactions. Ideally, our efforts should go a few steps beyond finding the most “trustworthy” shades of blue, or sprinkling little “lock” icons everywhere (though the latter doesn’t hurt).

Consumers’ concerns are multi-faceted, and fall into these four categories:

- the security of their bank account information

- usage of personally identifiable information

- control of when and how payments can be made

- contingencies for theft or loss of their device

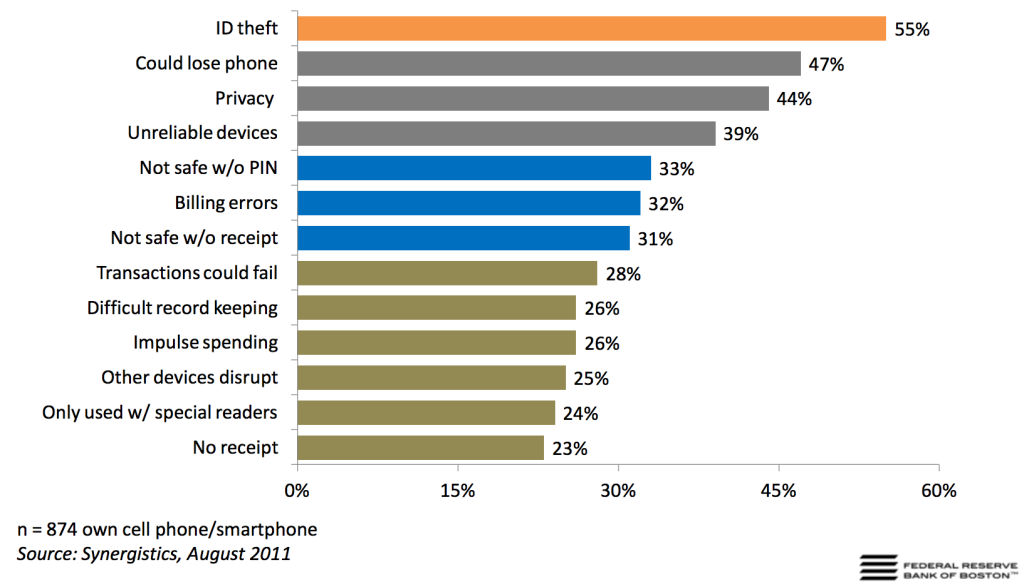

Designs that successfully address these four areas will imbue a holistic impression of trustworthiness in app’s experience. Falling short on any of these aspects will trigger doubts in the user’s mind. A recent report published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston reflects the four Trust Categories, chief among them being the exposure of their identity, and the fear of what might happen if their phone goes missing:

Figure 4-2: Consumers concerns related to using mobile devices for mobile, courtesy of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston[9].

Lets look at those first three responses to the survey, as they fairly inter-related. It’s clear that the surveyed consumers were most concerned with identity theft. It’s a truly frightening idea, that a thief could eavesdrop on or steal your phone, then learn everything about you: your name, your address, your relationships, your pictures, your credit card numbers, etc. This is why designers should take care never to display on-screen any information that would personally identify the user. The next concern was the loss of their device, which would trigger the first concern, identity theft, as well as the inconvenience of having to cancel any cards that might have been linked in some way to their phone. The third one, privacy, is a bit vague. Privacy could be the personal sense: who they are, where they live, or their phone number. In the financial sense, privacy could refer to their account numbers, balances and spending history. These are typical of the grave concerns that run through a user’s mind when they first encounter a new payment app, either seeing a friend using it, or seeing it their app store.

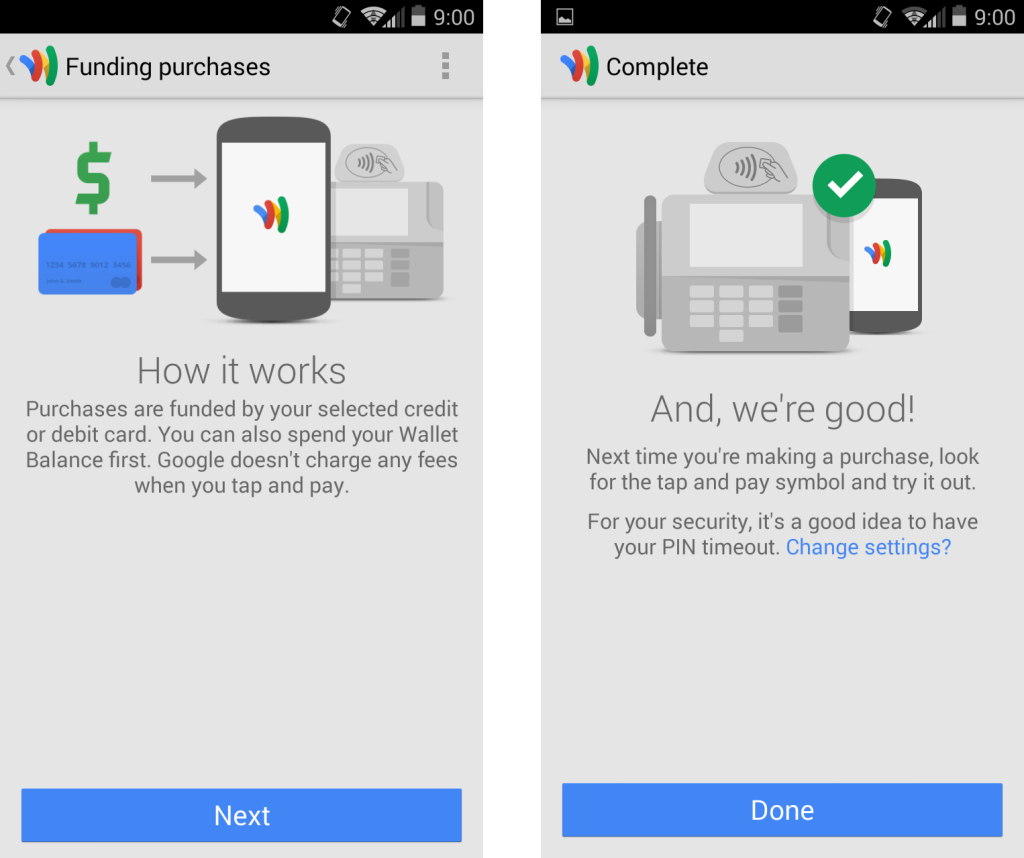

Google Wallet keeps the user informed during the process of setting up their phone for NFC payments, and uses helpful diagrams and explanations to explain how the feature works in the meantime (rather than a stock OS loader animation).

Financial privacy rights are heavily protected by global regulators (like the PCI Security Standards Council), especially around what we in the financial service industry call “cardholder data”: the cardholder’s name, card numbers, expiration dates, PINs, customer verification codes (the three digits on the back of the card). Industry security standards dictate that the most effective preventative measure against those three scenarios from occurring is the use of a consumer authentication factor. Asking a user to enter a password or PIN code is more often a welcomed task, rather than an annoyance. Even if a user doesn’t have an NFC wallet or PayPal on their phone, he or she is now likely more accustomed to using complex passwords (a mix of letters, numbers and symbols) as well as locking their phone with a passcode, gesture or fingerprint. They will expect any app that deals with their financial information to have similar affordances. You can never pay too much attention to the areas of an experience where users might have cause for concern.

Now, we will take a hard look at common pain points where mobile payment users feel the most uncertainty:

- onboarding and registration

- security options

- on-screen display of sensitive data

- getting help

These four interaction families are where the user is most likely to second-guess a financial app, especially if they encounter something unexpected. These complimentary use cases are what I like call the Bookends of the payment experience (signing up for the service, setting up their payment preferences, finding help when they have questions) and so its just as important to make them as seamless as possible. These use cases will most likely come in to play before the user even gets to the check out line.

[1] Ellsworth, The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions, 1994, pg 152

[2] NTT DoCoMo Report on Mobile Wallet programs 2008

[3] Did you know that 95% of ATMs in the U.S. run on Windows XP? Scary!

[4] Mitek, Mobile Deposit Case Study 2012

[5] Pew Research Center, The future of money, April 2012

[6] CNET: Stanford undergrads: iPhones are addictive, March 2010

[7] Javelin, 2013 Identity Fraud Report

[8] Unisys Security Index: U.S., Lieberman Research Group, May 13 2014

[9] Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Opportunities and Challenges in Broad Acceptance of Mobile Payments in the United States, July 2012, pg 17